Gantz Graf, et. al.

2024-01-31

An adventure through the works of Alex Rutterford

There’s something about music synchronisation that speaks to me on a fundamental level. Not music synchronisation as in the boring, business side of “find a popular song that kinda works with this video so we can use it in our commercial” - no, I mean the art of creating a video that synchronises so perfectly with a piece of music, that the video and the audio become one and the same, and that neither is complete without the other. It’s a rare feat to accomplish, and not something I’ve personally achieved yet - but it’s been done. Here’s a story about that.

Sometime during a lecture on digital arts last year, a discussion came up about IDM and glitch music. I didn’t get a good look at it at the time, but a few videos were shown in passing. One of them interested me enough to look it up myself, so that’s what I did - and it blew my mind.

Here, take a look (you’ll have to enable Youtube trackers):

So yeah. Gantz Graf by Autechre has what is possibly my favourite music video of all time. It’s unfortunate that there isn’t an official upload anywhere - this rip isn’t in great quality and it’s slightly out of sync, but it’s close enough that it can still be appreciated. Maybe I’ll buy a DVD and upload it myself.

The track itself is a complex, dense jungle of IDM with heavy syncopation and rapid, restless, ever-changing rhythms. And the video matches it, perfectly. Every distortion, every flash of geometry, every camera movement, every lighting change - all of it synchronises perfectly with some sound or another. The video invites you to break it down, to carefully watch the spasms of the contraption in the centre for patterns in movement and then carefully pick apart the mix until you find the auditory element that matches the visual one. And there’s always a match.

The attention to detail in this video, the depth of the fusion between light and sound into one singular experience, is unparalleled. The video looks exactly like how it sounds, down to each individual frame.

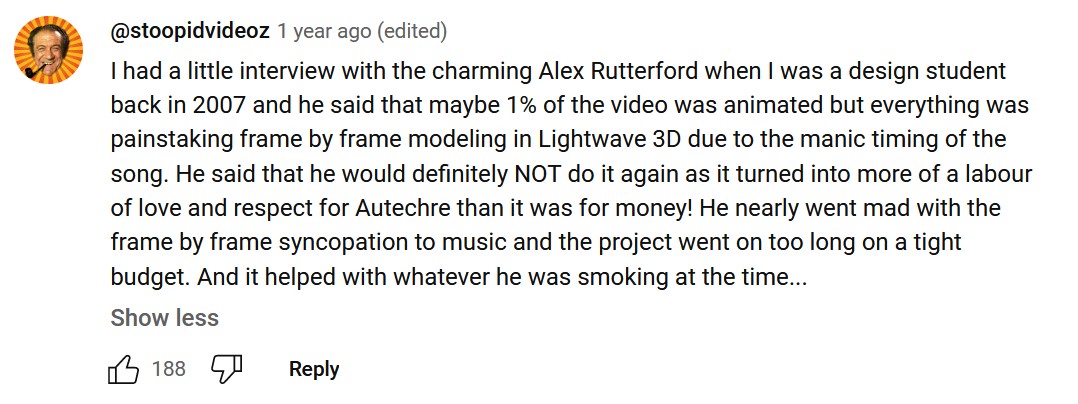

And it may be no surprise that each individual frame of the video feels so perfectly matched with the audio. A short browse through the comments section of this upload finds this:

Side note: although their authenticity can be hard to verify sometimes, YouTube comments are a brilliant and underappreciated source of anecdotes for just about anything under the sun, and there seems to be relatively little work done on analysing or archiving them. Something to think about.

This comment is very believable. No algorithm, no matter how clever, would have been able to make this video. Maybe if you had access to MIDI files representing every single instrument, you could make something that comes close, but only excruciating frame-by-frame animation could achieve this level of synchronisation with a piece of music this complex.

So, who is Alex Rutterford?

His Wikipedia page is relatively small, but it mentions some more projects he was involved in, and has a link at the bottom to this Warp Records interview on the Internet Archive.

In the interview, he discloses more details on his inspiration for the bizarre contraption in the video (a particularly vivid LSD trip which he wanted to recreate in at least some of its glory) and speaks a little bit more about the process of animating this beast:

I literally broke that track down into pages of numbers, like a wacky professor from the Muppet Show, Dr Bunsen. Sheets of paper with loads of numbers on them, (key frames). Although they weren’t random, they were related, indicative of certain parts of that scene, certain parts of that track. And I literally had to animate to those numbers, and keep rendering it off, and rechecking it and re-tweaking it to make sure everything worked in time, it’s that simple.

This confirms the YouTube comment: The whole thing was animated by hand. One thing missing from the interview is how long the whole process took, but just figuring out a workflow for producing the video apparently took “over a month”.

He also correctly predicts the shift of the filmmaking process towards increasing amounts of post-production, and laments about how anything created using CGI is inherently treated as “slick”, even this music video which he himself thinks of as dirty and grungy. (This interview was in 2002, and thankfully it seems that attitudes have shifted since then. Computers and computer graphics are, at this stage, just another tool in the artist’s toolkit - they can create any aesthetic, not just the slick and the futuristic.)

Anyway - what else has he made?

Let’s have a peek at some of Rutterford’s other work. He does a lot of graphic design, but I’ll be focusing on his videos here.

Unfortunately his films Sound Engine and 3space, made for the onedotzero arts organisation in 1998 and 2000, don’t seem to be available on YouTube. His third short film, Monocodes, is available - only in terrible quality, mind - but it features that same close, almost absolute link between audio and video and is still a delight to experience.

He has worked on commercials (despite saying in the 2002 interview that he didn’t really think he could) - and while most were difficult to track down, this 2005 advertisement for the PSP is a blast. I’m not quite sure what the… thing? creature?… has to do with the PSP except that it seemingly sheds media icons wherever it goes, but its movement is captivating - and again, impeccably in time with the hectic drum soundtrack. I particularly enjoy the moment about 34 seconds in where the second… thing… appears and starts swinging hyperspeed punches at the first to a semiquaver pattern in the tom-toms.

His music video for Amon Tobin - Verbal, a futuristic car chase, shows a similar care and attention to detail - the car flashes between different colours in time with the track’s vocal chops, the paint underneath and the lights overhead pass by in time with the snare drum, the vehicles collide with obstacles perfectly in time with the occasional extra percussion hit. There are more details than that, but I’ll let you figure those out ;)

Let’s talk about Radiohead

The first of Rutterford’s other works that I watched while researching this post was the video for Radiohead - Go To Sleep. Released in 2003, the video is quite different from Gantz Graf, but the skewed, slightly erratic camera movements identify it as being from the same director. I was surprised by how little synchronisation there was, though - especially when compared with Rutterford’s other work. It doesn’t even come close to evoking that same primordial feeling within me that I feel watching his other music videos.

Watching for a second time, I realised that it had been right in front of my face and I hadn’t seen it. The first half of the video actually follows the music closer than you might expect - leaves fall in front of the camera when a guitar chord is strummed, and during the chaotic camera movement though the crowd, people pass by the camera in time with the main guitar riff! That signature attention to detail is still there, if a little muted. But even that fades away in the second half… Was I missing something here?

Watching a few more times, it began to dawn on me that the connection still exists between music and video - but the way in which that connection is expressed is different. It’s not purely experiential like in Gantz Graf or Verbal, where the video is a direct extension of the audio and there’s a perfect mapping between sound and movement - it’s symbolic. The video represents less the sound itself, and more the concepts conveyed by the songwriting. There’s a layer of abstraction to it. The buildings crumble around the pedestrians, who sidestep the rubble, ignoring the apparent catastrophe and ignoring Thom Yorke’s cries about “monsters taking over”. But then they rebuild themselves, as if being rewound in time, and by the end of the video everything is back to how it was in the beginning. Was the catastrophe even real? Was this all just hysteria? A moral panic drummed up by the post-9/11 media landscape?

I’ll be honest - media analysis isn’t my strong suit. I’m sure I’ll get better at it in time, but I’ve always had difficulty deducing the inherent symbolic meaning of something, and often misinterpret the point completely. But I do enjoy learning about and discussing these things! So if you have an analysis, don’t be a stranger - I’ve a channel in my Discord server for talking about this stuff.

This symbolic connection is much more common in music videos than the direct, more “physical” one. I’m not sure how to feel about that. The latter has always felt more real to me, the connection more fundamental and plainly laid out. Am I just shallow? Would I be able to appreciate symbolic work better if I had an easier time picking apart its meaning?

I probably could, but I don’t think that inherently makes metaphorical videos more valuable than literal interpretations of the music. This is something I’d like to discuss more in the future, I have a lot to say on this. For now though, let’s keep working through Alex Rutterford’s videography-

Wait, what the heck is this?

…yeah. Rutterford’s most recent music video according to Wikipedia is for a song called Write This Down by UK alt-rock band Maximo Park. It’s… rather baffling, coming from him. The video is plain - it just consists of the band playing the song in a blank room. There are some CGI ribbons that follow the band members around at the places where each has the most active movement - the lead singer’s mic stand, the guitarists’ headstocks, the drummer’s drumsticks, and the pianist’s… hand? Which he waves about crazily in the air in a way that feels extremely forced, and kills me a little on the inside. It gives away that the whole point of this video is just to showcase this ribbon gimmick. Was that a novel thing at the time? I can only assume so, or otherwise I really don’t know what creative merit there is to be seen here.

This video came out in 2012, nine years after Rutterford’s previous music video. I’m going to make a bold take here - and it’s just a guess, but I really can’t think of a better explanation for this other than that he had little to no creative control over the video, and was roped in at least to some degree against his will. Or, hell - it might even be a mistake with the Wikipedia article itself. No sources are cited, and the video doesn’t mention who directed it.

Whatever the case may be, this video is from 2012. Sure, it happened well after the other videos in this article, but it can hardly be considered recent. So this begs the question:

What’s he up to these days?

Rutterford is currently a member of Embryogallery in New York City, alongside John Duncan, Edward Quist, Alan Vega and Ilpo Väisänen - each a legendary name in their own right, although my lack of culture shines through again: I haven’t heard of any of them! The gallery’s focus is, perhaps unsurprisingly, on “multimedia, cinema, video and sound design”. It’ll be a long while before I can make it out to New York, but if I ever do, I shall certainly pay a visit. I can excuse the NFTs as long as they don’t become a regular thing.

A couple of years ago, Alex Rutterford made an Instagram account! He’s been posting on there occasionally since then. All of his posts are short videos of 3D art with impeccable sound design and synchronisation - in fact, these little Instagram reels are the most evocative of the energy of Gantz Graf’s video since that video itself came out. (I like this one a lot!) Judging from his replies to inquisitive comments, his workflow consists of taking stems for whatever audio he’s using, deforming the geometry in different ways using those sounds , then doing lots of manual tweaking and post-processing to clean up the result. And apparently they’re all made in Lightwave 3D - the same software used to make the original Gantz Graf video. Interesting how things loop back on themselves like that.

Well, that was certainly a fun journey to take! I discovered quite a lot along the way, and hopefully so did you. This is my first post on here, so please do join my Discord server and have a chat if you’ve any thoughts! I hope to make this a semi-regular thing - one post a week, perhaps? If this was anything to go by, I have lots to learn about the things I like!